misc.

essay: does religion support or hinder peace?

12 Jan 2025

Last year, I won the Associateship of King's College London's Essay Prize for a short essay I wrote on free speech. You can read more about my surprise winning that prize here.

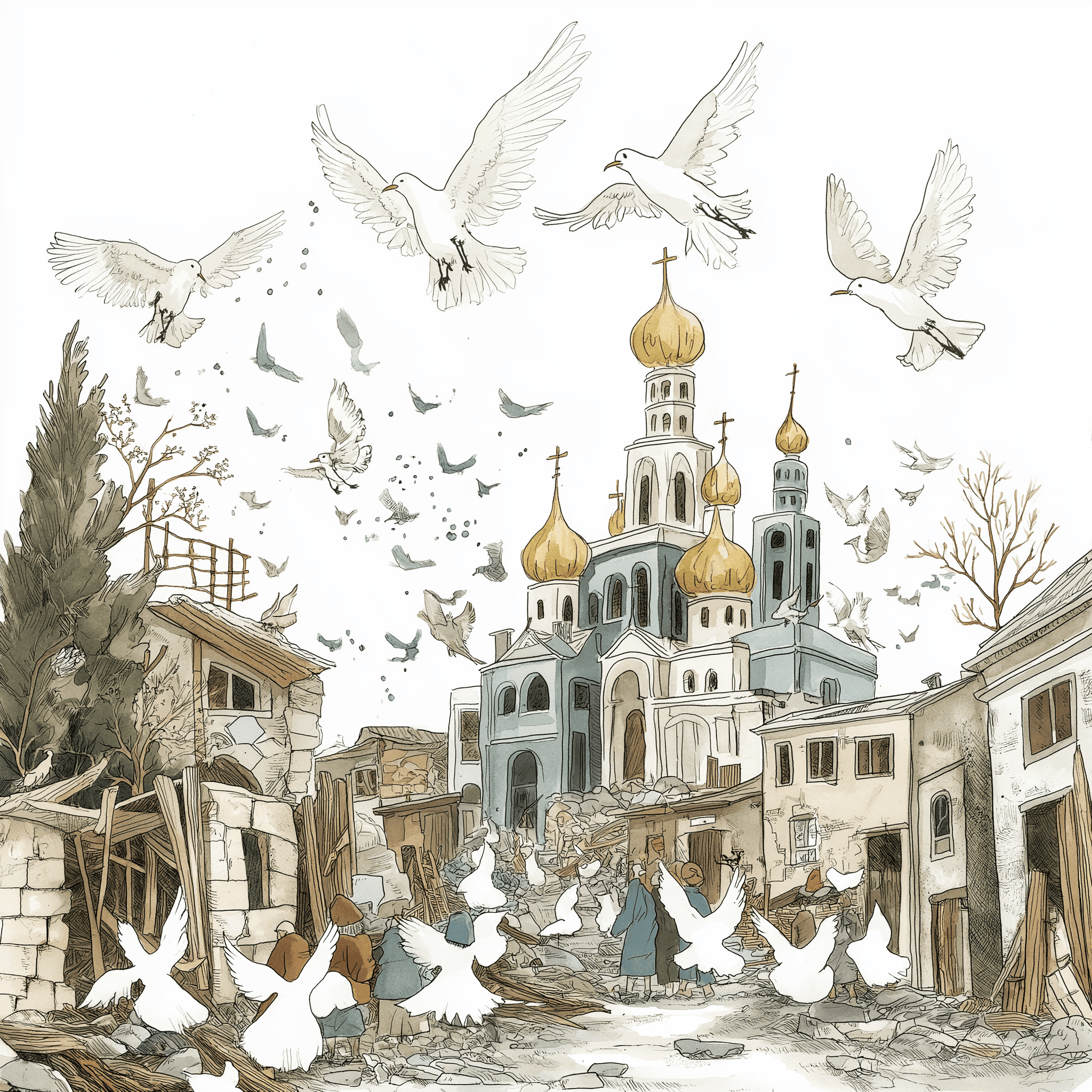

For this year's Associateship of King's College essay competition, we were asked to examine how religion supports or hinders the pursuit of peace, using an example from current or historic events to reinforce our argument. Below, you can read my short essay, which argues that religion has historically been used as a tool for both, with a particular focus on the Russia-Ukraine war. I hope you find it a compelling read.

Religion has arguably both supported and hindered peace more than any other single force in human history. While religion has historically offered humanity the moral and legal frameworks that cultivate peaceful co-existence, it has also been co-opted to justify war, as shown by the role the Russian Orthodox Church has played in the ongoing so-called “Holy War” in Ukraine. This essay will first examine the role of religion in supporting peace, providing some background on the intended role of religion by leaning on ideas from the likes of Hobbes to explore the moral underpinnings of jurisprudence. It will then draw from current events, using the example of Russia’s so-called “Holy War” in Ukraine, to argue that religion is exploited by states to provide a divine or moral reinforcement to geopolitical directives. As such, religion holds an incredibly influential role as both a force for peace and unity, as well as for conflict and war.

The core principles of the world’s major religions inherently promote peace. The ‘Golden Rule’, for example, which says to treat others as you would like to be treated and which promotes peace through discouraging hostility and encouraging reciprocity, appears in Christian (The Holy Bible, Luke 6:31, n.d.), Hindu (The Mahabharata, 5:1517, n.d.), and Buddhist (The Udana-Varga, 5.18, n.d.) thought, to name just a few. Religion promotes moral virtue not only within its adherents but also through them, both as they set examples for others -- in applying principles like the ‘Golden Rule’ – and via proselytism. It can therefore be said that religion disseminates not just a framework for a peaceful life, but also for a peaceful world.

Religion supports peace by underpinning our jurisprudence, providing us with an alternative to the ‘state of nature’ in which peace cannot exist. In Chapter 13 of Hobbes’ (1651) Leviathan he talks about what he calls the “war of everyone against every one” that defines the state of nature where, with no social contract, individuals act solely according to their own desires. Hobbes argues that the state of nature is “nasty, brutish, and short” (ibid.), making it intolerable and suggesting that the only viable alternative is to enter into a social contract. Under this social contract, we sacrifice certain freedoms in favour of broader societal order, with laws laid out that are designed to preserve peace. Historically, religion has provided both a divine and moral foundation to these laws, reinforcing the belief that all actions are observed and judged by a higher power, ensuring individual accountability and encouraging obedience. Additionally, shared religious values can contribute to the formation of a collective culture and identity, which are both crucial for fostering respect for the social contract and its legal structures (Theodosiadis and Vavouras, 2023). As such, religion not only supports peace but also legitimises the social contract, making peace not just possible, but perhaps providing the only viable and sustainable path to it.

While religion has historically played a central role in enabling and fostering peace, it has also been co-opted to justify violence and provide a divine foundation for war. This duality is symbolic of a cardinal tension within the very concept of religion and religious narratives, where peaceful ideologies are often shaped to serve violent political agendas. A striking example from contemporary affairs is the ongoing war in Ukraine, where the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) has lent religious legitimacy to the Kremlin’s framing of the conflict as a ‘Holy War’. This so-called moral crusade claims to protect ethnic Russians living in Ukraine from the ‘Satanism’ of the West. However, this justification is tenuous at best: ethnic Russians comprise just a small minority of Ukraine’s population (17.3% per the most recent Census data in 2001, after which questions around ethnicity were dropped from official sources) (State Statistics Service of Ukraine, 2001), and nearly a third of Ukrainians do not identify with Eastern Orthodoxy at all (Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 2023). By espousing a war that prioritises the interests of a minority while disregarding the religious and cultural diversity of Ukraine, the ROC reveals the superficiality of its moral claims. The extent to which religion is being weaponised to mask geopolitical ambitions is clear – the war is reframed not as an aggressive attempt to gain power, but as a righteous mission to protect a minority.

This narrative casts the war as a binary struggle between good and evil, leaving no room for negotiation or peaceful compromise. The role of religion in striking this rigid dichotomy only serves to deepen the rift between Russia and Ukraine and fuels international tensions, significantly hindering any chance for peace in the process. In particular, Patriarch Kirill’s endorsement of the war has elevated the conflict beyond a territorial and political dispute, instead framing it as a battle between Russia’s moral righteousness and the West’s moral corruption. By labelling the West’s liberal values, such as LGBTQ+ rights and the feminist movement, as ‘Satanic’, Kirill has imbued the war with a particularly acute religious and ideological urgency that bypasses the traditional diplomatic channels associated with conflict. This transformation of the war into a spiritual struggle shifts the focus away from peaceful negotiation or diplomatic resolution and replaces it with an all-or-nothing narrative. In doing so, Kirill reinforces the idea that compromise is not just necessary, but morally impermissible (Kivelson and Worobec, 2023). This rhetoric doesn’t just deepen the ideological rift between Russia and Ukraine, but also aligns religious identity with political allegiance, further entrenching the divisions within both countries (and indeed among global powers). The ‘moral crusade’ narrative leaves little space for dialogue, and by casting the West – and by extension, Ukraine – as embodiments of evil, it delegitimises any effort for peaceful conflict resolution.

Scholars such as Piskorski (2023) suggest that the Russian Orthodox Church is becoming increasingly difficult to govern in its current state, with its survival contingent on Russia’s successes in subjugating other Orthodox-led ex-Soviet states. This perspective highlights how, in some cases, the politics in religion (as opposed to the religion in politics) may compel institutional leaders to prioritise war over peace in order to combat the “centrifugal forces” (ibid.) found within their faith. As a result, in the case of the Russian Orthodox Church, this has led to church leaders not “thinking about…victims of the war” (ibid.). If the internal dynamics of religious institutions at times require conflict for their survival, it could be argued that religion is inherently at odds with the promotion of peace. Furthermore, the role of the Russian Orthodox Church’s role in the war in Ukraine illustrates the additional danger posed by intertwining religion with nationalism. Scholars like Brubaker (2012) argue that this kind of fusion fosters ‘us versus them’ narratives, where national and religious unity are framed as inseparable, which delegitimises pluralism and coexistence. In Ukraine, Russia and the ROC’s invocation of Orthodox Christianity as such a defining feature of its national identity (Klyuchkovska and Klyuchkovska, 2022) excludes non-Orthodox Ukrainians and those aligned with the Kyiv Patriarchate, portraying them as both cultural and spiritual outsiders. This exclusionary rhetoric does not just alienate large groups of Ukrainians, but it also escalates the conflict as it erodes the possibility of shared identity or mutual understanding – both key prerequisites for peace. It’s not just the case that the politics of religion can at times demand conflict for its survival; the intertwining of religion with nationalist politics can also more subversively deepen divisions and undermine the foundations for peaceful coexistence.

In conclusion, religion plays a dual role in both supporting and hindering peace. The core principles of the world’s major religions, such as the ‘Golden Rule’, encourage peace through norms of empathy and reciprocity, while religion has historically underpinned legal frameworks that provide us with a viable alternative to the ‘state of nature’. Adhering to a social contract that is empowered by religious ethics has allowed humans a more peaceful coexistence, and shared religious values play a role in strengthening collective identity which contributes to societal order.

However, as the Russian Orthodox Church’s involvement in the war in Ukraine illustrates, religion has also been manipulated to serve geopolitical agendas, turning faith into a tool for legitimising violence. The rhetoric of this ‘Holy War’ reframes the conflict into a spiritual struggle, which reduces the room for a peaceful dialogue or resolution. The Church’s endorsement of the war, in conjunction with its fusion of religion and nationalism, has deepened divisions both within Ukraine itself and globally, further entrenching the ideological rift between East and West. This manipulation highlights the dangers of intertwining religion with political power, which can significantly hinder our prospects for peace.

Ultimately, the example of the ROC’s involvement in the war in Ukraine underscores the complex role that religion can play in both fostering and hindering peace, as it demonstrates how religious narratives can be manipulated to justify conflict and deepen divisions. While religion’s potential for fostering peace remains strong, its weaponisation for political ends reveals to us a deeper tension and duality: religion can either be used to build bridges, or to fortify walls.

References

Brubaker, R., 2012. Religion and nationalism: Four approaches. Nations and Nationalism, 18(1), pp. 2–20. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275113115_Religion_and_Nationalism_Four_Approaches [Accessed 30 December 2024]

Hobbes, T., 1651. Leviathan: or, The matter, form and power of a commonwealth ecclesiastical and civil. London: Andrew Crooke

KIIS, 2023. Public opinion in Ukraine on the Russian Orthodox Church. Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. Available at: https://archive.ph/20230125023508/https://kiis.com.ua/?lang=eng&cat=reports&id=1129 [Accessed 30 December 2024]

Kivelson, V.A. and Worobec, C.D., 2023. Satanism and Exorcism in Contemporary Russian Rhetoric. Cornell University Press. Available at: https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/satanism-exorcism-contemporary-russian-rhetoric-kivelson-worobec-02-2023/ [Accessed 30 December 2024]

Klyuchkovska, I.S. and Klyuchkovska, O.V., 2022. The national identity and Orthodox Church: The case of Ukraine. East European Business and Economics Journal, [online] 6(1), pp.14-28. Available at: https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/ebce-2022-0014 [Accessed 30 December 2024]

Piskorski, J., 2023. Why the Russian Orthodox Church supports the war in Ukraine. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2023/01/why-the-russian-orthodox-church-supports-the-war-in-ukraine?lang=en [Accessed 30 December 2024]

State Statistics Service of Ukraine, 2001. General results of the census: National composition of the population. All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001. Available at: https://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/results/general/nationality/ [Accessed 30 December 2024]

The Holy Bible. (King James Version). (n.d.). Luke 6:31

The Mahabharata. (n.d.). Book 5, Section 1517

Theodosiadis, M. and Vavouras, E., 2023. Religion as a means of political conformity and obedience. Religions, 14(9), p. 1180. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/14/9/1180 [Accessed 30 December 2024]

The Udana-Varga. (n.d.). Verse 5.18