product

the quadrants of knowledge and making decisions

30 Dec 2023

TL;DR

There are four permutations of knowledge and lack thereof

Each of these combinations represents a cognitive trait - Knowledge, Awareness, Bias, and Ignorance

Understanding where danger lays here and not focusing too much on any single one of the quadrants is how to become a balanced person both professionally and personally

A note on knowledge and making decisions.

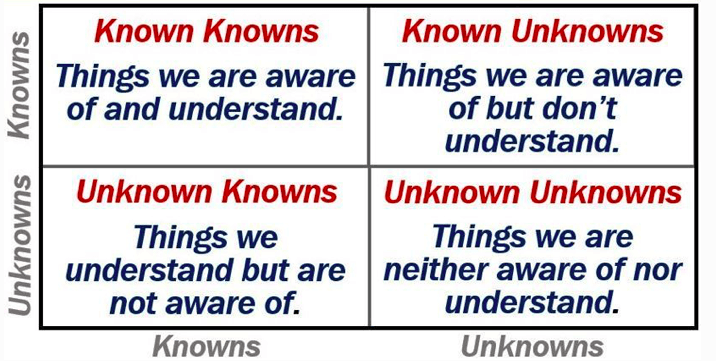

This is a famous quadrant comparing knowns and unknowns. As you’ll see, there can be four combinations: Known Knowns, Known Unknowns, Unknown Knowns, and Unknown Unknowns.

Just writing that has induced a sense of semantic satiation about the word ‘known’ for me, so if you’re seeing this for the first time and feeling a little put off, don’t worry. The reason I want to dig into these is because thinking about, or perhaps more so being aware of, this taxonomy and keeping it front of mind can be useful not just in work but also in every day life.

They represent Knowledge, Awareness, Bias, and Ignorance, which are the four buckets of knowledge in which all information sits for an individual.

Known Knowns

Known knowns are our little comfort zone. As humans, we spend a lot of our cognisant mental activity living in and thinking about known knowns. These are the things we are aware of and understand.

Known Unknowns

Known unknowns are the interesting ones for me. Personally, I’m quite comfortable with there being things I’ll never know, but I find it much harder to knowingly have a gap in my knowledge and to not be driven to fill it. For me, most of the time this just looks like me bookmarking Wikipedia articles, or setting half-hearted reminders on my phone to “google Benford’s Law after dinner tomorrow”. Known unknowns are the things we are aware of but don’t understand. These are gaps we can fill, or things we can note to be aware of and dig into more when making relevant decisions.

Unknown Knowns

The unknown knowns are an interesting space. These are things we understand but are not aware of. In product, my engineers and I often convert unknown knowns into known knowns when deep-diving on a new feature. We’ll be breaching a new area, thinking we’re starting from the ground floor. Quickly, we realise we actually have a lot of implicit knowledge on what our approach should be. But unknown knowns are also where bias lives. They can be influencing the ways we’re framing or thinking about problems.

Unknown Unknowns

Finally, the unknown unknowns. This is ignorance. It’s things we’re neither aware of nor understand. There’s a lot of unknown unknowns. Not just between individual human beings but also for humans collectively. The fields of space exploration, medicine, physics, and philosophy come to mind when thinking about unknown unknowns. The noumenal word, as Kant would have it, contains a ton of data we’re just not aware of. And there’s plenty of things we have observed that we haven’t made sense of just yet.

Now known knowns and unknown knowns, ie. Knowledge and Awareness, feel a pretty safe space. Knowledge the most so. We should be questioning our perception of our known knowns, and seeking to convert unknown knowns to known knowns as we live and grow as humans. But for the most part, this area of the knowledge quadrant is pretty cosy.

It’s the bottom two quadrants that are most dangerous, and it just so happens that this is where we as humans tend to spend far less time and effort.

History is strewn with examples of suboptimal outcomes arising from people being led by unknown knowns (biases). For example, the engineers working on the Chernobyl nuclear reactor knew that there were design flaws with the system, but didn’t realise just how catastrophic the outcomes could be from these flaws in the right scenario. The knowledge they had was implicit in their experience designing the reactors, but they weren’t actively aware of these flaws until the disaster played out. Or take Titanic, for example. Anyone with a sheet of paper and a pencil could work out that the number of lifeboats multiplied by their respective capacity was not enough to save the ship’s passengers and crew. But both aesthetic preferences and the Merchant Shipping Act of 1894, which only required ships of the Titanic’s size to carry 16 lifeboats, meant that this fairly obvious issue was overlooked. They were complying with legal requirements, effectively outsourcing this thought to the law (ie. “If we needed more lifeboats, it would be legal for us to have more”) and so focused instead on allowing passengers to have unobstructed views off the decks. These unconscious biases are dangerous, and not just in physical products where lives are at risk. Biases exist everywhere and range from harmless to existential. Fortunately, with practice and rigour, we can deconstruct and analyse many of our biases to ensure the unknown knowns are brought forth into known knowns for relevant decisions.

Personal anecdote: If you know me, you know I’m an advocate for accessible development. Making software products that can be used by as many people as possible. We all know that someone who is blind can’t see. This fact is a known known. It feels stupid to even say it. But when it comes to designing our latest product, how often do we think about how the blind might be using it? In this arena, the fact that blind people can’t see, and therefore can’t use a product that doesn’t have haptic or sound based communication, instead becomes an unknown known. It’s rarely thought of when making design decisions. Accessible development, or rather lack thereof, is one area where biases associated with unknown knowns are rife, and it’s something we need to combat. Only through raising its profile and constantly banging the drum can we bring things front of mind and turn them into known knowns when making decisions.

Unknown unknowns are a rocky outcrop. I see unknown unknowns as the birthplace of humility. Through recognising that there are unknown unknowns, we realise that our known knowns do not comprise the entire story, and that there could be information out there that could change how we think or feel about something. It’s not bias so much as it is instead a tool to expose bias, and an impetus to hold your opinions strongly but loosely. This humility is an important perspective to bring to interactions in both the professional and personal settings. Think to yourself: Is there any information I could be shown that would change how I’m thinking about this? If no, what is the reason for my level of conviction in this opinion/decision? These questions are aimed at revealing bias. Then, by actually asking those around you for that extra information, or seeking out possible pieces of relevant information for yourself, you can discover some unknown unknowns and bring them into the happy areas of the quadrant - our knowledge and awareness sections.